Rembrandt & the medium of etching

A colloquium conducted at QCA, Brisbane 28 May 2022 Sponsored by

Presentation by Prof Ross Woodrow followed by demonstration/discussion with Master Printers Dr David Jones and Gwenn Tasker

selection of illustrations from the first manual on etching by Abraham Bosse in 1662

The first comprehensive manual on etching in Europe [Treaty of ways to engrave in silver and brass. By means of strong waters, and hard and soft varnishes. Set of the way to print the plates & to build the press, & other things concerning the said arts, ] was published by Abraham Bosse (1602 - 1676) in Paris in 1645 when Rembrandt was well established as an etcher. The subsequent adaptions of this manual, such as the example in English by William Faithorne (1616 - 1691), published in 1662 in London, follow the Bosse publication closely and the illustrations are copied, although often lacking the quaility of the originals. The first English version is available on Archive and linked below.

This manual is a delight to read (when you get used to the old English lower case “s” looking like an “f” especially here where they are unusually both often given serifs so cutting off the usual lower sweep of the “s”. Only the “f” has the cross bar so it’s not that difficult once you get used to it.

Aqua Fortis, used throughout, is acid (mostly nitric, always for the alchemists) but you will see the term seems to be generic for any acid mixture including the far less toxic one: (vinegar, salt, ammonium chloride, and copper sulphate). The Dutch mordant mix we use (Hydrochloric plus water and a dash of potassium chloride) was not developed until the middle of the nineteenth century. Interestingly the acid was poured over the plate from a glazed ceramic jug and into a glazed ceramic trough below – again illustrated, in the manual. This was done over and over, with rotating of the plate every few minutes on the network of lugs holding it.

The basics haven’t changed much since then. The methods of transferring designs onto plates are much as today – even includes a recipe for making tracing paper. Most interesting, to answer the usual question of how long to soak paper – the recommendation was to always soak your paper overnight. Given that editions would often be in hundreds the paper would have to remain moist for a day at least. As is noted, if the paper was left at the end of the day it should be soaked again the next night.

This is the second 1702 edition also available in Archive with the addition on how to make and use the press, again taken from Bosse.

The following Rembrandt etchings will be examined and discussed. They are arranged here in chronological order of production, spanning the years 1630 to 1642, the most productive period of Rembrandt’s career.

Rembrandt’s renown as a painter only started to overshadow the reputation for his etchings about a century after his death. As his biography shows he was a most prolific and innovative etcher establishing the expressive potential for the medium, at a time when reproductive prints of paintings were increasingly dominating the market. His interest was in etching as an indEpendent medium.

Some of Rembrandt’s etchings, like many other prints published between 1400 to 1900, have abrevations in Dutch, Latin, Spanish and other languates that define the status of the print, publisher and artist who made it. A comprehensive glossary of these abbreviations is available for download in this PDF. Rembrandt printed and published his own prints so only have authorship claimed usually just with his signature.

Some additional information below on the prints shown.

This etching was made the year Rembrandt’s father died. A prosperous miller and a supportive father of nine children, Harmen Gerritszoon van Rijn (1568–1630) was the model for numerous paintings and etchings by Rembrandt. In this etching, he is wearing a Middle Eastern-inspired cap. During the 1630s, Rembrandt, who was “intrigued by the Middle East”, depicted many of his subjects wearing Middle Eastern garments. “By the early seventeenth century the commercial enterprises of Dutch merchants had reached the Middle East, so exotically dressed foreigners were a familiar sight in the streets and marketplaces of Amsterdam. Exotic attire became a fashion fad, and Dutch men, including Rembrandt himself, would sometimes be portrayed wearing similar outfits.”

Interestingly, the family name of “van Rijn” is a Dutch “toponymic surname meaning ‘from (the) Rhine River.’” Ref: Wiki; The Met (NY); NGA (USA). Purchased from Josef Lebovic Gallery, Sydney

Above description from Lebovic catalogue. Plate is in a US private collection (as at 2014).

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) The Baptism of the Eunuch 1641

etching with touches of drypoint, 1641, but a later impression of New Hollstein's final state (of four), on laid paper, platemark 182 x 210 mm sheet 190 x 219 mm even toning to the sheet, with faint damp-staining to upper section Literature: Hind 182; New Hollstein 186 iv/iv

Description from British Mus: Self-portrait of Rembrandt, in a flat cap and embroidered dress, bust facing front; posthumous third state with signature re-worked; from an edition of the Recueil published by Henri Louis Basan around 1810. c. 1642. The 2006 label for "Rembrandt: a 400th anniversary display": Self-portrait in a flat cap, c.1642 Etching, Hind 157, only state

Three impressions are shown of this small but characterful self-portrait. The weaker impression at the lower right (BM number 1879-10-11-199) may have been printed after his death. Seen in bright sunlight, Rembrandt wears an old-fashioned jerkin and a beret, perhaps his studio attire, and seems to scrutinize himself as though looking at a stranger.

Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606–1669)

Man In A High Cap [Portrait Of Rembrandt’s Father]1630/c1800 impression. etching and drypoint initialled and dated in plate upper left, 10.1 x 8.5cm. Ref: Bartsch #321/iii/iii, Hind #22/iii/iii, Nowell-Usticke #321/v/vi.

Provenance: Josef Lebovic Gallery, Sydney

Description from BM: Bust of a man wearing a high cap (the artist's father?), three-quarter length, almost in profile to right, wearing a turban; posthumous fifth state with additional diagonal shading on the centre of the turban, before additional lines on the temple and cheek.1630 Etching and drypoint

The story of the baptism of the eunuch is from Acts 8:26-39. While walking along the road from Jerusalem to Gaza, St. Philip is compelled by the spirit of God to accompany the passing entourage of the Treasurer of Ethiopia, a eunuch serving under Candace, Queen of Ethiopia. Philip joins them and preaches to the official and his servants, and when they come to a small body of water, the eunuch asks Philip to baptize him.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) Self-Portrait in a Flat Cap and Embroidered Dress

Etching, circa 1642, a later impression of New Hollstein's final state (of three), printing with plate tone on cream laid paper, platemark 94 x 63 mm Literature: New Hollstein 210 iii/iii

During Rembrandt’s early career the most admired European printmaker, indeed image maker, was Jacques Callot (French, c.1592-1635). Callot worked almost exclusively with etching and had no interest in, or reputation for, making paintings. He is the first artist in the western tradition to attain great wealth as well as reputation with a singular career making prints and produced around 1400 plates in his lifetime. This is about four times the number for Rembrandt, although Rembrandt’s inventory is impressive enough considering his output as a painter.

We consider examples from Callot’s most famous series the Miseries of War from 1633 which contained 17 plates detailing the impact of war on soldiers and the general population. Original Callot examples are compared with Dutch copies from the 1670s.

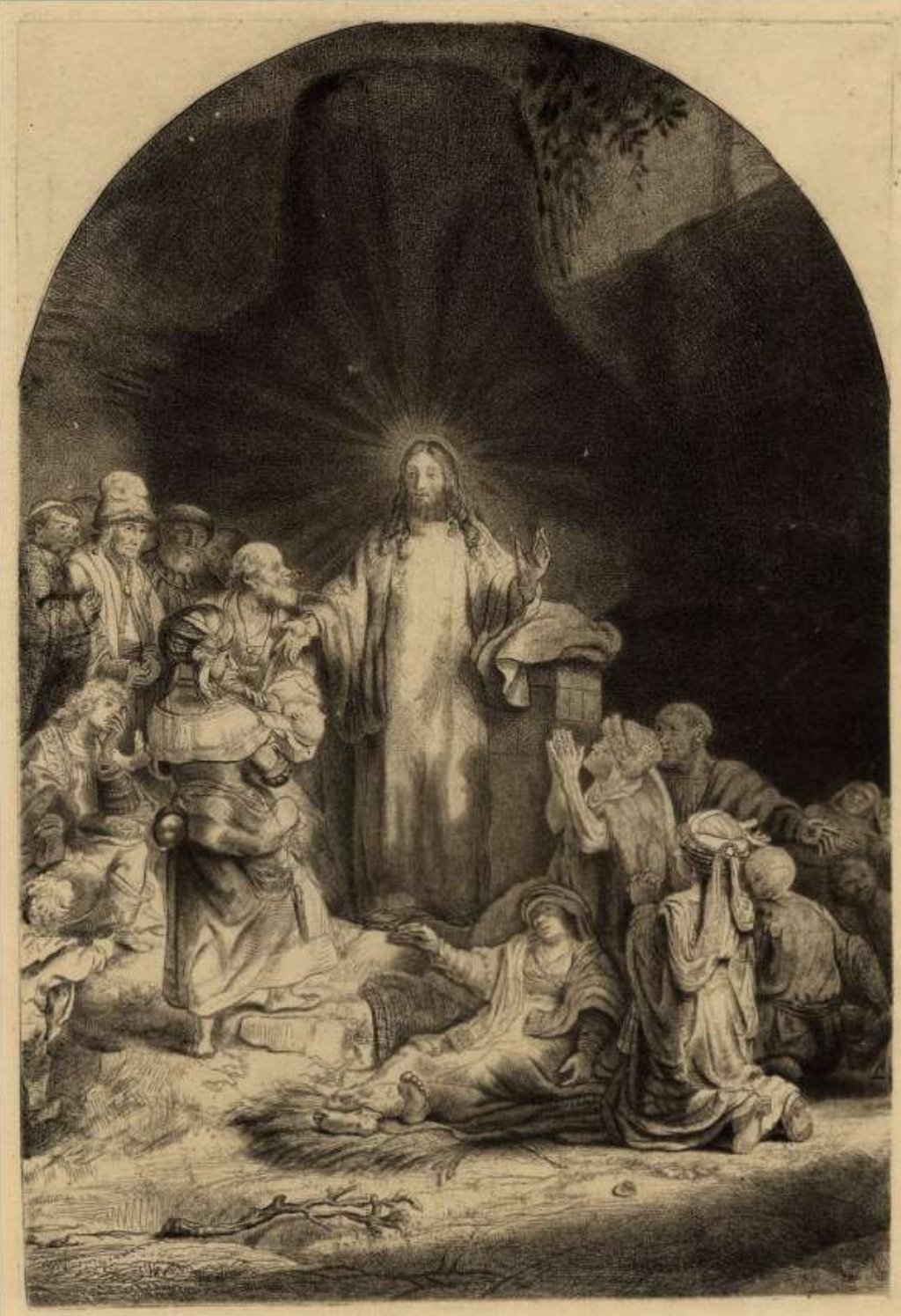

We are showing proof and counter-proof of Rembrandt’s plate that once belonged to Captain William Baillie (1723-1810) who apart from being a war hero was a highly skilled etcher and engraver who famously re-worked a number of Rembrandt’s plates in the 1770s.

In this coloured etching by James Gillray (1807), Captain William Baillie is represented by the figure in the foreground looking through reversed glasses. Much has been made of Baillie’s involvement with Rembrandt’s plates but the story is never as simple as it appears. The Gillray print shown is also a great example of the commercial application of etching in the late eighteenth century, for the rapid publication of topical caricature and satire.

Baillie acquired three of Rembrandt’s plates from 1775 and before this he had done a number of etchings in the “manner” of the artist based on Rembrandt drawings. His acquisition of the plate for Rembrandt’s so called “Hundred Guilder print” caused a sensation at the Royal Academy when he showed a print from the original worn-out plate next to his complete re-working. These rich new impressions were to be a very limited, naturally also expensive edition. Rembrandt’s final life-time state is in the British Museum along with two examples of Baillie’s reworking. All are linked below. Things turned from wonder to dismay for most critics and commentators when Baillie decided to make the plate produce new editions with the most brutal strategy of cutting it up. The results are below with links to the originals in the BM.

The cut plates below are obviously not to scale but dimensions are below.

Baillie’s treatment of the Goldweigher plate is probably less controversial as he seems to have cleaned and clarified it for reprinting.

In this proof and counter-proof of the first state the face was left blank as Rembrandt was waiting to get a sitting with Uytenbogaert - Receiver-General of Holland. Several other examples of the blank face sheets exist and three with charcoal sketches in the space without the face.

The Goldweigher (Jan Uytenbogaert) etching and drypoint 1639. c. 25 x 20 cm

The British Museum has an example with face touched in with chalk: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_F-6-54

and a counter-proof with outlines of facial features worked in, BM: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_F-6-55

BM also has 2nd state with face complete: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_F-7-79 “Annotated in unknown hand in ink below platemark: ‘Capt. Baillie certifys this[...]engraved by Rembrandt in 1639’ -".

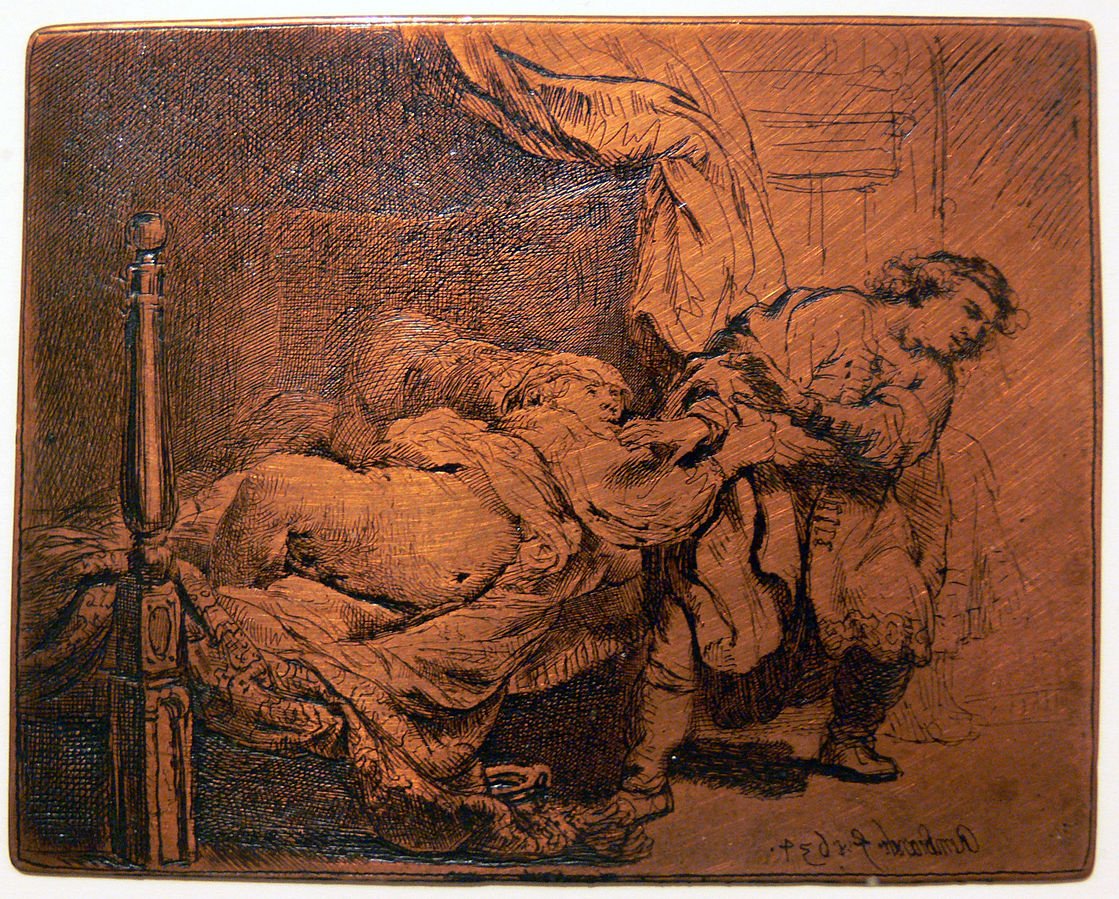

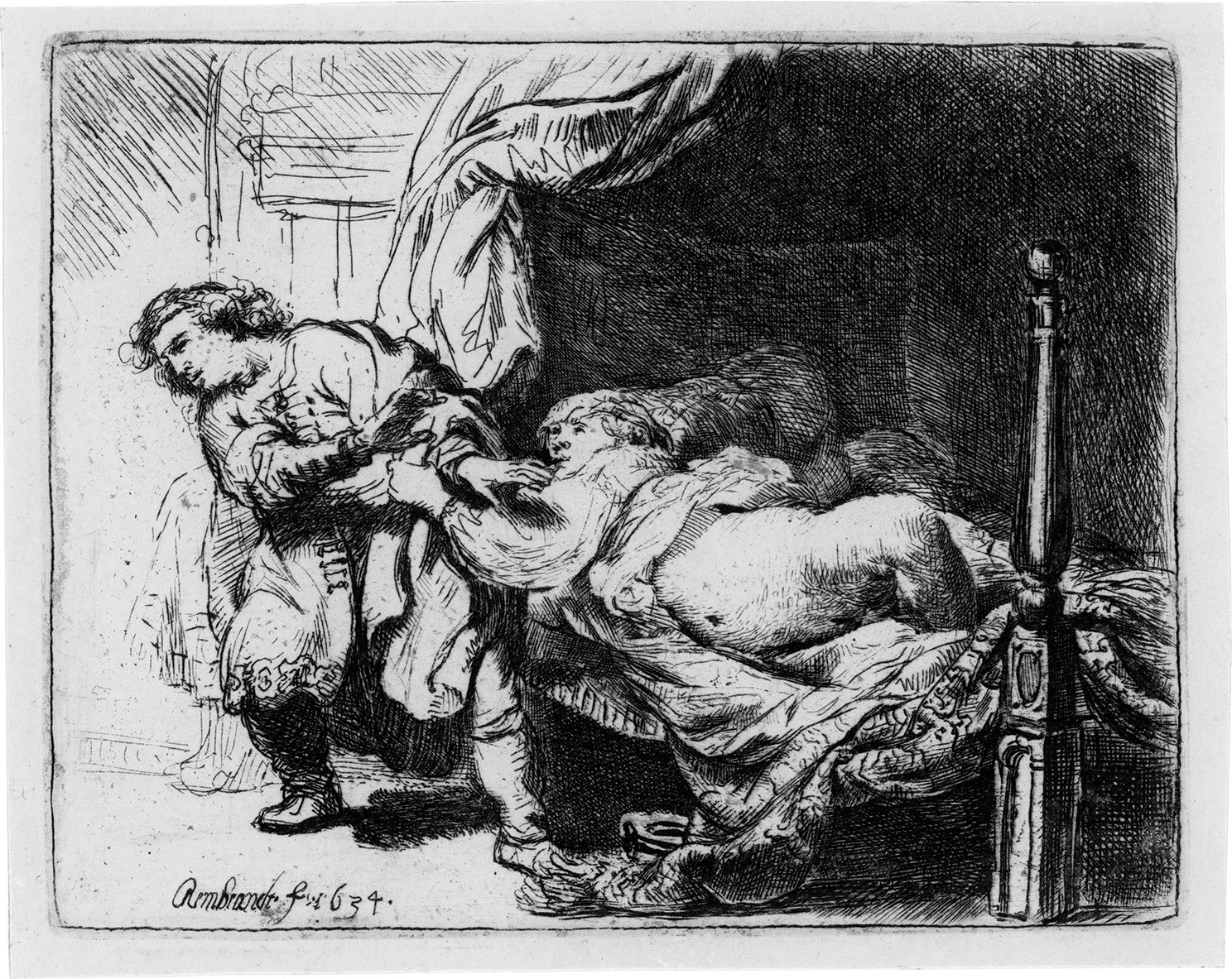

The Goldweigher is the only one of the Rembrandt plates owned by Baillie that has survived. It is held in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Below is the plate used to print the impression of Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife. It is on permanent loan to the Rembrandthuis Museum in Amsterdam. A high-res image is available for open use on the creative commons.

There are a number of dealer websites that give summaries of Rembrandt’s surviving copper plates, however the definitive study is: “The History of Rembrandt's Copperplates, with a Catalogue of Those That Survive” by Erik Hinterding in Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art Vol. 22, No. 4 (1993 - 1994), pp. 253-315 (63 pages) Published By: Stichting Nederlandse Kunsthistorische Publicaties. If you do not have access to a University or other subscription the PDF can be accessed here for study purposes only.

Selected etchings from the nineteenth and twentieth century will be shown including:

Francisco de Goya (1746-1828). Disparate Pobre (Poor Folly) [Two Heads are Better than One], plate 11 from Los Proverbios 1864 [plate worked 1816 -23] etching, burnished aquatint, drypoint and burin, 25 x 35 cm

Plate 11: two headed woman looking back towards cowled figure, but approaches group of old women on steps. [BM description] (Second ed printed at Real Academia of Fine Arts San Fernando, Madrid.)

Copyright © Ross Woodrow --All Rights Reserved 2022/23

![Man In A High Cap [Portrait Of Rembrandt’s Father]1630/c1800 impression. Etching, initialled and dated in plate upper left, 10.1 x 8.5cm.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b9e00fd506fbe9caf83a4b6/1653451027915-0ECHI9WGSCGYWILPBBWG/Untitled-1.jpg)

![Old Man with Beard, Fur Cap, and Velvet Cloak, [circa 1631] etching with drypoint, impression of New Hollstein's second state (of three).](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b9e00fd506fbe9caf83a4b6/1653450517388-WPDS08KZLR8OQICB4SIZ/secondState.jpg)

![Gerrit van Schagen (Dutch, c. 1642 – 1690) after Jacques Callot (French, 1592 – 1635) The Hanging. Plate11 from De Droeve Ellendigheden van den Oorloogh [The sad miserableness of the war] c.1670](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b9e00fd506fbe9caf83a4b6/1653572215369-DV0JPS7ZP0NC80TVF5ZB/JCmis-11.jpg)

![Gerrit van Schagen (Dutch, c. 1642 – 1690) after Jacques Callot (French, 1592 – 1635) Discovery of the criminal soldiers plate 9 [The sad miserableness of the war] c.1670](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b9e00fd506fbe9caf83a4b6/1653572478423-7OJB1JVX2ALG9Z2MRIG4/CallotCopy-soldiers.jpg)