Rembrandt & the expressive potential for etching

Royal Queensland Art Society presentation by Prof Ross Woodrow

8 February 2026 @ 2:00 pm - 4:00 pm

This will be a materially focussed discussion with only original prints used as examples. Discussion will follow comparative examinations of different techniques, styles and intentions in the following sequence.

Discussion of contrasting examples of mediums: using woodcuts, plate engravings and etchings from 1500s to early 1600s.

Examination of work by Rembrandt’s leading contemporaries highlighting influence, digression and innovation.

Comparison of Rembrandt’s self-portrait with Kathe Kollwitz’s self-portrait both etched when the artists were around 40 years of age but the production separated by 273 years. How do they see themselves and how did others see the role of the artist in those different centuries?

The process as a unique expressive mode with the potential to operate outside the demands of mimetic or naturalistic representation.

Conclusion: Historically, etching has been seen as a medium where contour and tonal contrast have primacy over colour and colour based aerial perspective. As a result, it was accepted that only with difficulty could an etching render the phenomenal world. However, it has proved uniquely suited to evoke ideas, generate the imaginary and states of mind that cannot be expressed in descriptive language. Rembrandt is the first to fully understand this primary synthetic power of the medium.

Resources and references follow

Catalogue for my recent (2023/24) etching exhibition in Singleton and Newcastle: Etching: Rembrandt’s Legacy SACC 2023 ISBN: 978-0-646-88334-2. An extensive online resource was also created for the exhibition giving information on the Print Trade in Rembrandt’s time and the developing distinctions in printmaking between reproduction of paintings, printed illustrations and etching as an innovative independent expressive medium.

We know a good deal about the techniques used in Rembrandt’s etching practice, not only from the direct evidence of his remaining plates and prints, but also because various manuals on etching were published during, and soon after, his lifetime and, in at least one case, specifically quoting the type of ground Rembrandt used on his copper plates.

selection of illustrations from the first manual on etching by Abraham Bosse in 1662

The first comprehensive manual on etching in Europe [Treaty of ways to engrave in silver and brass. By means of strong waters, and hard and soft varnishes. Set of the way to print the plates & to build the press, & other things concerning the said arts, ] was published by Abraham Bosse (1602 - 1676) in Paris in 1645 when Rembrandt was well established as an etcher. The subsequent adaptions of this manual, such as the example in English by William Faithorne (1616 - 1691), published in 1662 in London, follow the Bosse publication closely and the illustrations are copied, although often lacking the quaility of the originals. The first English version is available on Archive and linked below.

This manual is a delight to read (when you get used to the old English lower case “s” looking like an “f” especially here where they are unusually both often given serifs so cutting off the usual lower sweep of the “s”. Only the “f” has the cross bar so it’s not that difficult once you get used to it.

Aqua Fortis, used throughout, is acid (mostly nitric, always for the alchemists) but you will see the term seems to be generic for any acid mixture including the far less toxic one: (vinegar, salt, ammonium chloride, and copper sulphate). The Dutch mordant mix we use (Hydrochloric plus water and a dash of potassium chloride) was not developed until the middle of the nineteenth century. Interestingly the acid was poured over the plate from a glazed ceramic jug and into a glazed ceramic trough below – again illustrated, in the manual. This was done over and over, with rotating of the plate every few minutes on the network of lugs holding it.

The basics haven’t changed much since then. The methods of transferring designs onto plates are much as today – even includes a recipe for making tracing paper. Most interesting, to answer the usual question of how long to soak paper – the recommendation was to always soak your paper overnight. Given that editions would often be in hundreds the paper would have to remain moist for a day at least. As is noted, if the paper was left at the end of the day it should be soaked again the next night.

This is the second 1702 edition also available in Archive with the addition on how to make and use the press, again taken from Bosse.

The following manual was first published the year of Rembrandt’s death in 1669. The edition available to read on Archive is the second 1675 edition.

Browne, Alexander, (active 1660-1677) Ars pictoria: or An academy treating of drawing, painting, limning, etching. To which are added XXXI. copper plates, expressing the choicest, nearest, and most exact grounds and rules of symmetry. Collected out of the most eminent Italian, German, and Netherland authors. By Alexander Browne, practitioner in the art of limning

On page 106 “The ground of Rinebrant of Rine” is his off-handed claim that Rembrandt only used white ground. “but be sure you do not heat the plate too hot when you lay the ground on it, and lay your black ground very thin, and the white ground upon it, this is the only way of Rinebrant.” Material evidence in Rembrandt’s surviving preliminary drawings for etchings show at least one backed by black charcoal dust as would be expected for transfer onto a white ground but other transfer sheets are backed with white lead as with the standard transfer to dark grounds. In other words, the only certainty is Rembrandt used both white and dark grounds.

This manual does not recommend pouring acid over the plate or dipping the plate in an acid bath but describes building a wall of wax around the edges of the plate. This was done by creating a roll of warmed green soft wax long enough to reach around all edges of the plate where it is flattened into a wall about “half and inch” (c2 cm) high to hold the “aqua fortis” nitric acid which is poured onto the plate from a glass - noting the deeper the acid the better the bite. If biting too savagely, the acid could be diluted with vinegar. It is well established from the evidence on the plates, that Rembrandt generally trimmed the edges of the copper after the etching was complete, which suggests that he used this method mostly for his small etching plates since the external border of copper would offer a non-intrusive base for the wax wall. Using a glass of acid makes more logical sense than setting up a large bath or the significant machinery as needed with pouring, especially as Rembrandt never produced a high volume production of plates at any point in his career. Some of his etching show lines blocked out by bubbles which has been interpreted as Rembrandt using an acid bath, but the same masking bubbles would appear during the use of wax walls for the acid.

The Rembrandt etchings discussed are here arranged in chronological order of production, spanning the years 1630 to 1642, the most productive period of Rembrandt’s career.

Rembrandt’s renown as a painter only started to overshadow the reputation for his etchings about a century after his death. As his biography shows he was a most prolific and innovative etcher establishing the expressive potential for the medium, at a time when reproductive prints of paintings were increasingly dominating the market. His interest was in etching as an indEpendent medium.None of his contemporaries comes close to him in the number of counterproofs and different states he produced. Like rembrandt, collectors came to value the unique properties of different variations in the creation of an etching.

Some of Rembrandt’s etchings, like many other prints published between 1400 to 1900, have abbreviations in Dutch, Latin, Spanish and other languages that define the status of the print, publisher and artist who made it. A comprehensive glossary of these abbreviations is available for download in this PDF. Rembrandt printed and published his own prints so only have authorship claimed usually just with his signature.

Some additional information below on the prints shown.

This etching was made the year Rembrandt’s father died. A prosperous miller and a supportive father of nine children, Harmen Gerritszoon van Rijn (1568–1630) was the model for numerous paintings and etchings by Rembrandt. In this etching, he is wearing a Middle Eastern-inspired cap. During the 1630s, Rembrandt, who was “intrigued by the Middle East”, depicted many of his subjects wearing Middle Eastern garments. “By the early seventeenth century the commercial enterprises of Dutch merchants had reached the Middle East, so exotically dressed foreigners were a familiar sight in the streets and marketplaces of Amsterdam. Exotic attire became a fashion fad, and Dutch men, including Rembrandt himself, would sometimes be portrayed wearing similar outfits.”

Interestingly, the family name of “van Rijn” is a Dutch “toponymic surname meaning ‘from (the) Rhine River.’” Ref: Wiki; The Met (NY); NGA (USA). Purchased from Josef Lebovic Gallery, Sydney

Above description from Lebovic catalogue. Plate is in a US private collection (as at 2014).

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) The Baptism of the Eunuch 1641

etching with touches of drypoint, 1641, but a later impression of New Hollstein's final state (of four), on laid paper, platemark 182 x 210 mm sheet 190 x 219 mm even toning to the sheet, with faint damp-staining to upper section Literature: Hind 182; New Hollstein 186 iv/iv

Description from British Mus: Self-portrait of Rembrandt, in a flat cap and embroidered dress, bust facing front; posthumous third state with signature re-worked; from an edition of the Recueil published by Henri Louis Basan around 1810. c. 1642. The 2006 label for "Rembrandt: a 400th anniversary display": Self-portrait in a flat cap, c.1642 Etching, Hind 157, only state

Three impressions are shown of this small but characterful self-portrait. The weaker impression at the lower right (BM number 1879-10-11-199) may have been printed after his death. Seen in bright sunlight, Rembrandt wears an old-fashioned jerkin and a beret, perhaps his studio attire, and seems to scrutinize himself as though looking at a stranger.

Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606–1669)

Man In A High Cap [Portrait Of Rembrandt’s Father]1630/c1800 impression. etching and drypoint initialled and dated in plate upper left, 10.1 x 8.5cm. Ref: Bartsch #321/iii/iii, Hind #22/iii/iii, Nowell-Usticke #321/v/vi.

Provenance: Josef Lebovic Gallery, Sydney

Description from BM: Bust of a man wearing a high cap (the artist's father?), three-quarter length, almost in profile to right, wearing a turban; posthumous fifth state with additional diagonal shading on the centre of the turban, before additional lines on the temple and cheek.1630 Etching and drypoint

The story of the baptism of the eunuch is from Acts 8:26-39. While walking along the road from Jerusalem to Gaza, St. Philip is compelled by the spirit of God to accompany the passing entourage of the Treasurer of Ethiopia, a eunuch serving under Candace, Queen of Ethiopia. Philip joins them and preaches to the official and his servants, and when they come to a small body of water, the eunuch asks Philip to baptize him.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) Self-Portrait in a Flat Cap and Embroidered Dress

Etching, circa 1642, a later impression of New Hollstein's final state (of three), printing with plate tone on cream laid paper, platemark 94 x 63 mm Literature: New Hollstein 210 iii/iii

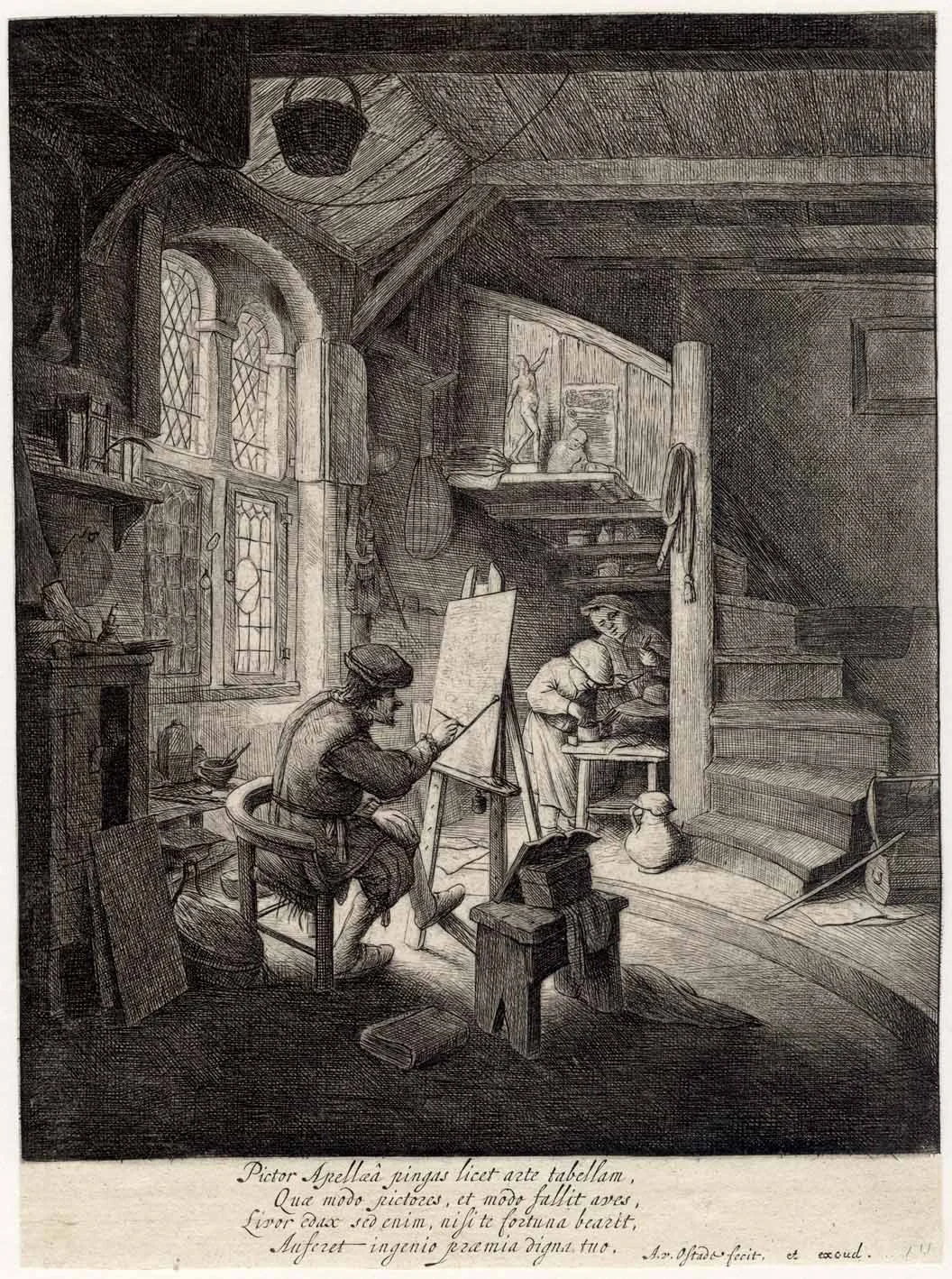

The other great Dutch painter/etcher contemporary of Rembrandt was Adriaen van Ostade (Dutch, Haarlem 1610–1685 Haarlem) Here is his largest and most famous etching. The Painter in His Studio c. 1667 (The 1670 edition includes the lines of verse.) Etching on laid paper This is an eighteenth-century printing of the final state. c. 23.4 x 17.4 cm Inscribed below the image borderline: “Pictor Apellieâ pingas licet arte tabellam, / Quae modo pictores, et modo fallit aves, / Livor edax sed enim, nisi te fortuna bearit, / Auferret ingenio praemia digna tuo. / A. v. Ostade fecit.”

(Translation by Oliver Phillips: “Though you a painter, paint a painting with Apelles’ art which now fools painters, and now the birds. Yet, gnawing envy, unless fortune bless you, will take away the prizes worthy of your talents.”)

During Rembrandt’s early career the most admired European printmaker, indeed image maker, was Jacques Callot (French, c.1592-1635). Callot worked almost exclusively with etching and had no interest in, or reputation for, making paintings. He is the first artist in the western tradition to attain great wealth as well as reputation with a singular career making prints and produced around 1400 plates in his lifetime. This is about four times the number for Rembrandt, although Rembrandt’s inventory is impressive enough considering his output as a painter.

We consider examples from Callot’s most famous series the Miseries of War from 1633 which contained 17 plates detailing the impact of war on soldiers and the general population. Original Callot examples are compared with Dutch copies from the 1670s.

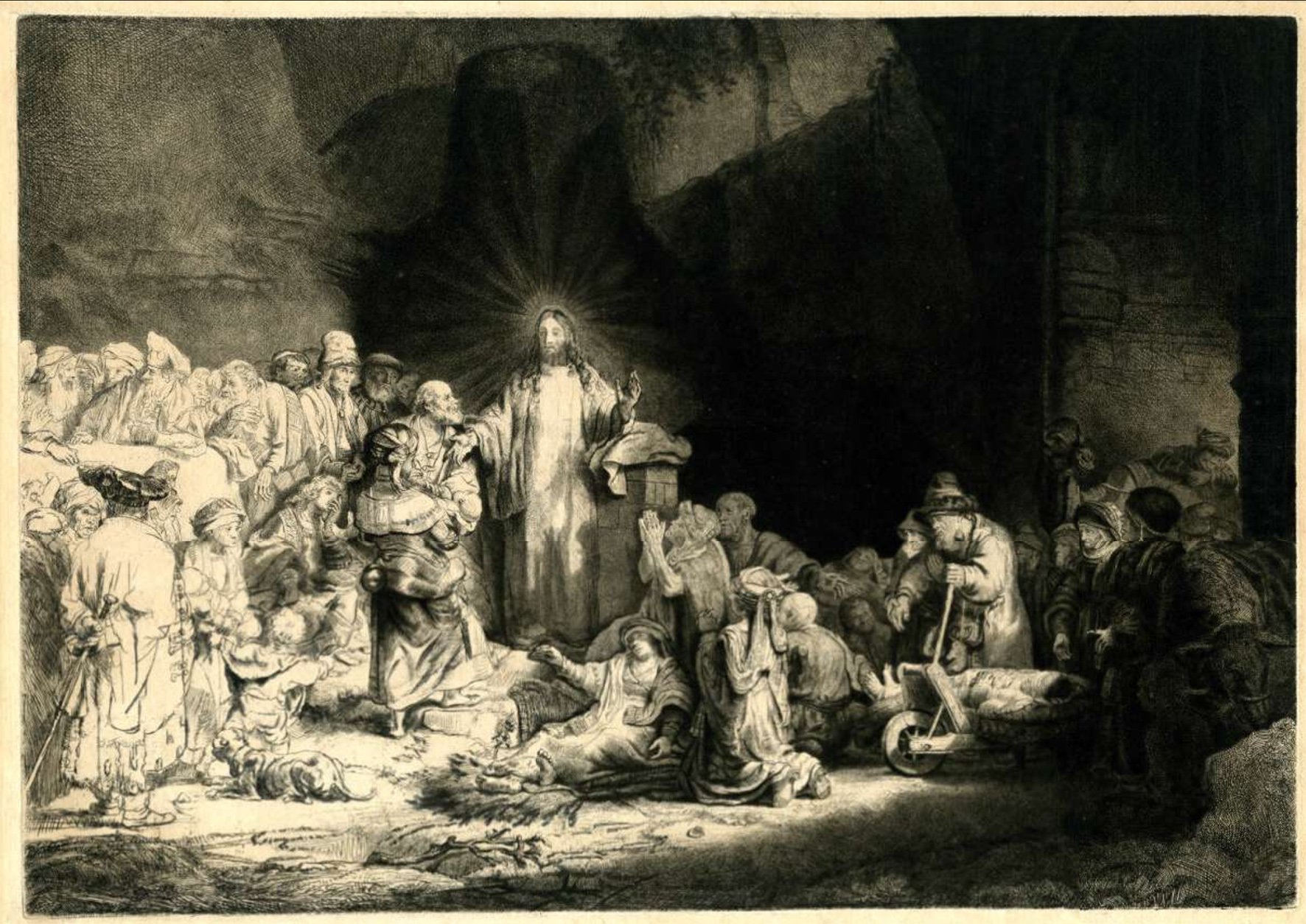

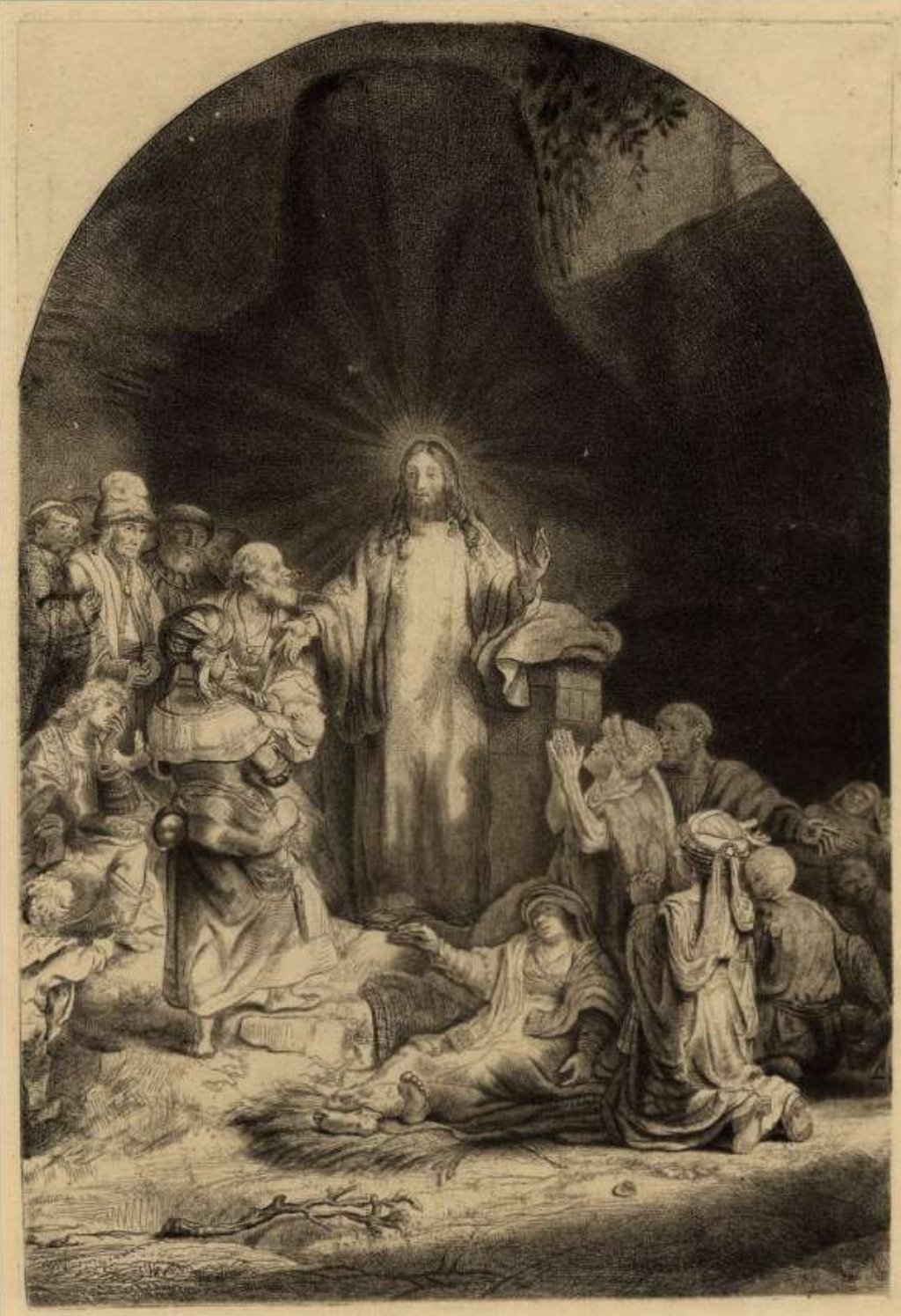

The proof and counter-proof of Rembrandt’s plate shown, once belonged to Captain William Baillie (1723-1810) who apart from being a war hero was a highly skilled etcher and engraver who famously re-worked a number of Rembrandt’s plates in the 1770s.

In this coloured etching by James Gillray (1807), Captain William Baillie is represented by the figure in the foreground looking through reversed glasses. Much has been made of Baillie’s involvement with Rembrandt’s plates but the story is never as simple as it appears. The Gillray print shown is also a great example of the commercial application of etching in the late eighteenth century, for the rapid publication of topical caricature and satire.

Baillie acquired three of Rembrandt’s plates from 1775 and before this he had done a number of etchings in the “manner” of the artist based on Rembrandt drawings. His acquisition of the plate for Rembrandt’s so called “Hundred Guilder print” caused a sensation at the Royal Academy when he showed a print from the original worn-out plate next to his complete re-working. These rich new impressions were to be a very limited, naturally also expensive edition. Rembrandt’s final life-time state is in the British Museum along with two examples of Baillie’s reworking. All are linked below. Things turned from wonder to dismay for most critics and commentators when Baillie decided to make the plate produce new editions with the most brutal strategy of cutting it up. The results are below with links to the originals in the BM.

The cut plates below are obviously not to scale but dimensions are below.

Baillie’s treatment of the Goldweigher plate is probably less controversial as he seems to have cleaned and clarified it for reprinting.

In this proof and counter-proof of the first state the face was left blank as Rembrandt was waiting to get a sitting with Uytenbogaert - Receiver-General of Holland. Several other examples of the blank face sheets exist and three with charcoal sketches in the space without the face.

The Goldweigher (Jan Uytenbogaert) etching and drypoint 1639. c. 25 x 20 cm

The British Museum has an example with face touched in with chalk: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_F-6-54

and a counter-proof with outlines of facial features worked in, BM: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_F-6-55

BM also has 2nd state with face complete: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_F-7-79 “Annotated in unknown hand in ink below platemark: ‘Capt. Baillie certifys this[...]engraved by Rembrandt in 1639’ -".

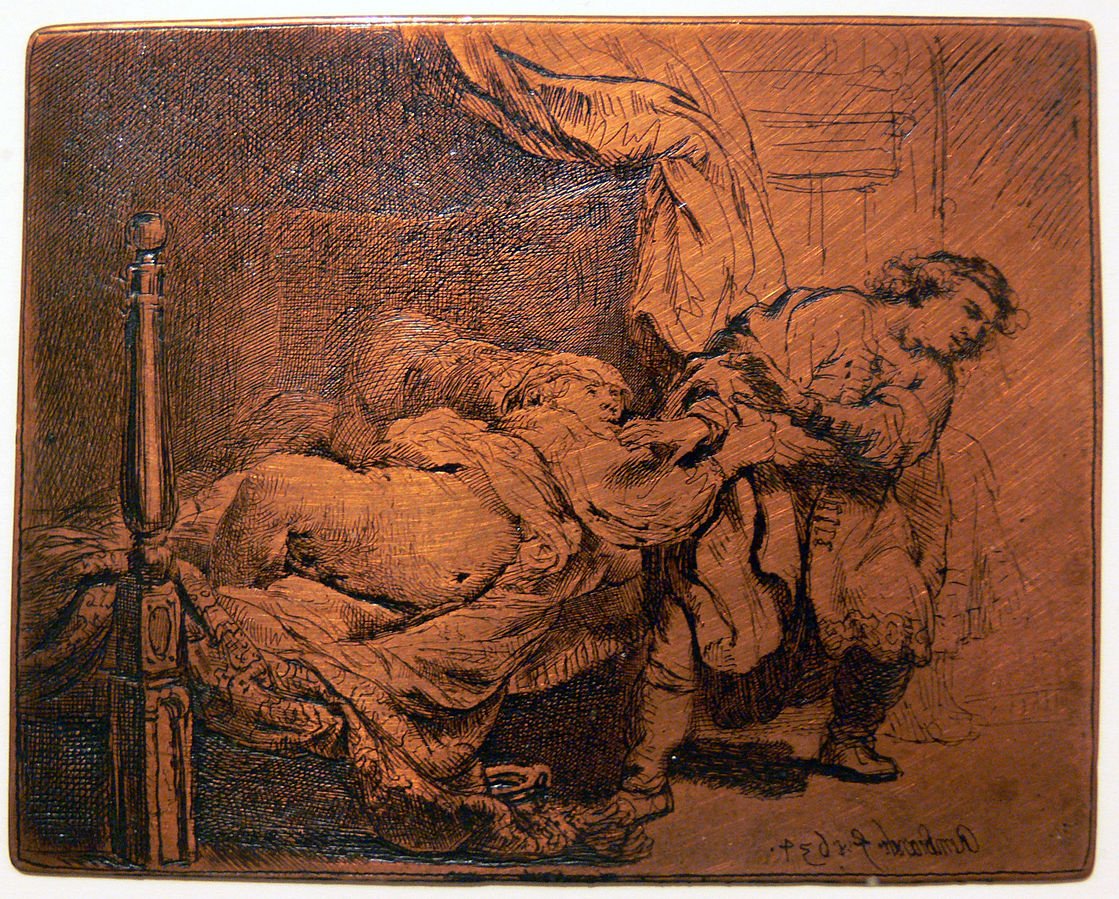

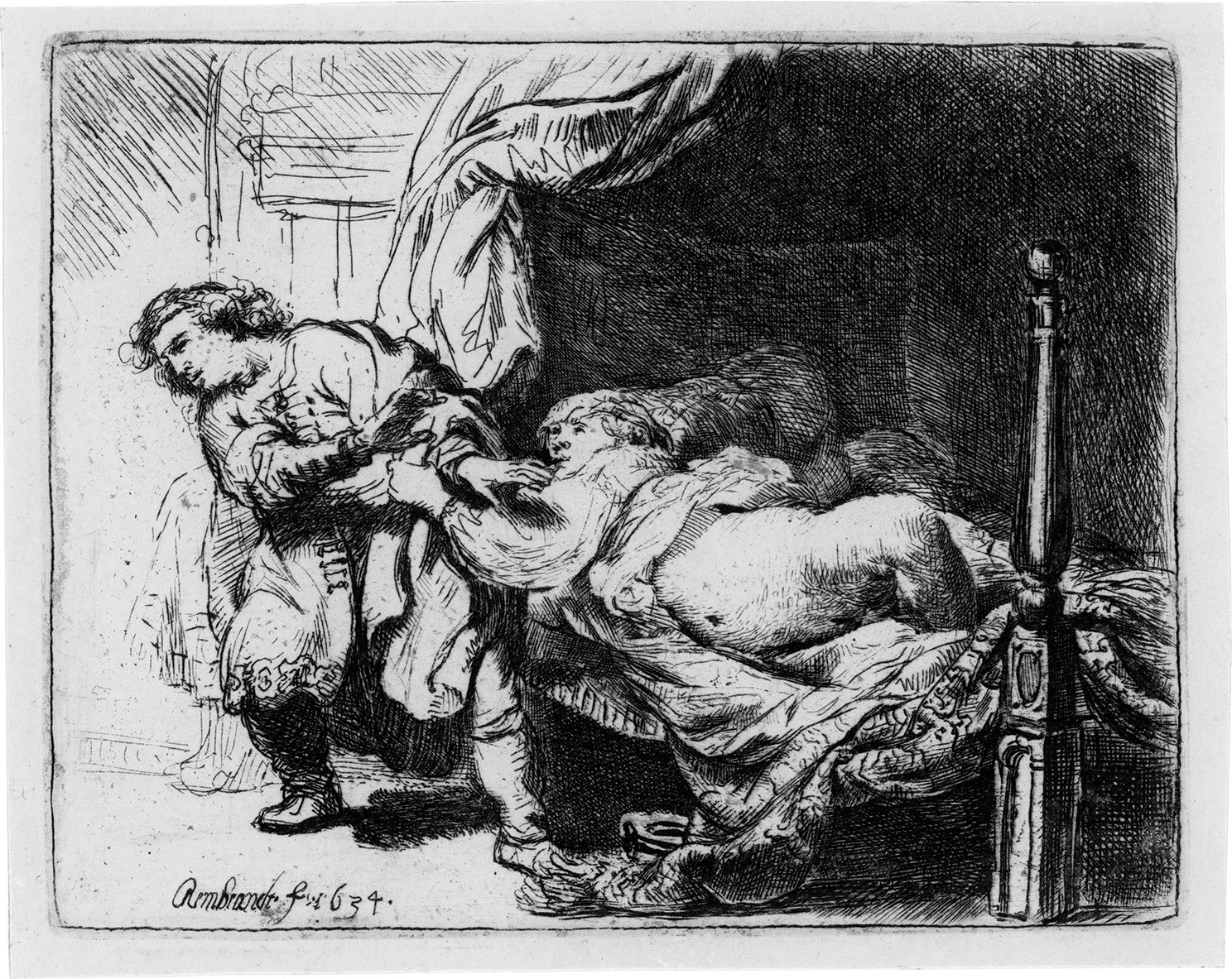

The Goldweigher is the only one of the Rembrandt plates owned by Baillie that has survived. It is held in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Below is the plate used to print the impression of Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife. It is on permanent loan to the Rembrandthuis Museum in Amsterdam. A high-res image is available for open use on the creative commons.

There are a number of dealer websites that give summaries of Rembrandt’s surviving copper plates, however the definitive study is: “The History of Rembrandt's Copperplates, with a Catalogue of Those That Survive” by Erik Hinterding in Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art Vol. 22, No. 4 (1993 - 1994), pp. 253-315 (63 pages) Published By: Stichting Nederlandse Kunsthistorische Publicaties. If you do not have access to a University or other subscription the PDF can be accessed here for study purposes only.

Details of prints by sixteenth century artists shown are below.

Hans Baldung Grien (c. 1484 –1545) was considered the most gifted student of Albrecht Dürer. The Virgin with the child on the grassy bench c. 1506 Leaf size: c. 23.0 x 16.0 cm. Good, old impression on laid paper with part of a watermark. It was formerly attributed to Dürer (Bartsch VII.178.13 (Appendix)). The artist created this woodcut in the time when he was working in Dürer’s studio in Nuremberg (from 1503 to about 1507). Hollstein 65.II (with the Durer monogram that was added later)

Marcantonio RAIMONDI (after Dürer) (1480-1527) Fall of Man c. 1512 Engraving c.12.6 x 10cm (block one after Title sheet of Small Passions) trimmed to edge of image

Johann Mommard. (1560–1631) 1/37 Fall of Man

Anonymous artist, Incunable leaf with coloured woodcut from the Life of Saints of Voragine (Augsburg: J. Schönsperger, 1499) coloured woodcut showing Saint an original leaf from Voragine's 'Heiligenleben' with Stephen. Pope Stephen I (Latin: Stephanus I; died 2 August 257) was the bishop of Rome from 12 May 254 to his death in 257. Leaf size: c. 23.5 x 16.5 cm / woodcut: c. 8 x 6 cm

Marcantonio Raimondi (Italian, Argini (?) ca. 1480–before 1534 Bologna (?))After Albrecht Dürer (German, Nuremberg 1471–1528 Nuremberg)

The Circumcision of Christ from the cycle The Life of the Virgin 1506-1510 engraving c. 29.7 X 21.7 cm.

Selected etchings from the eighteenth to twentieth century will be shown including:

Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki (Danzig, Poland 1726 - Berlin 1801) Two Standing Ladies (Demoiselles Quantin) 1758 Plate size 14 x 9.2 cm sheet 18 x 12 cm etching and drypoint on laid paper signed and dated in the plate. (Engelmann 10)

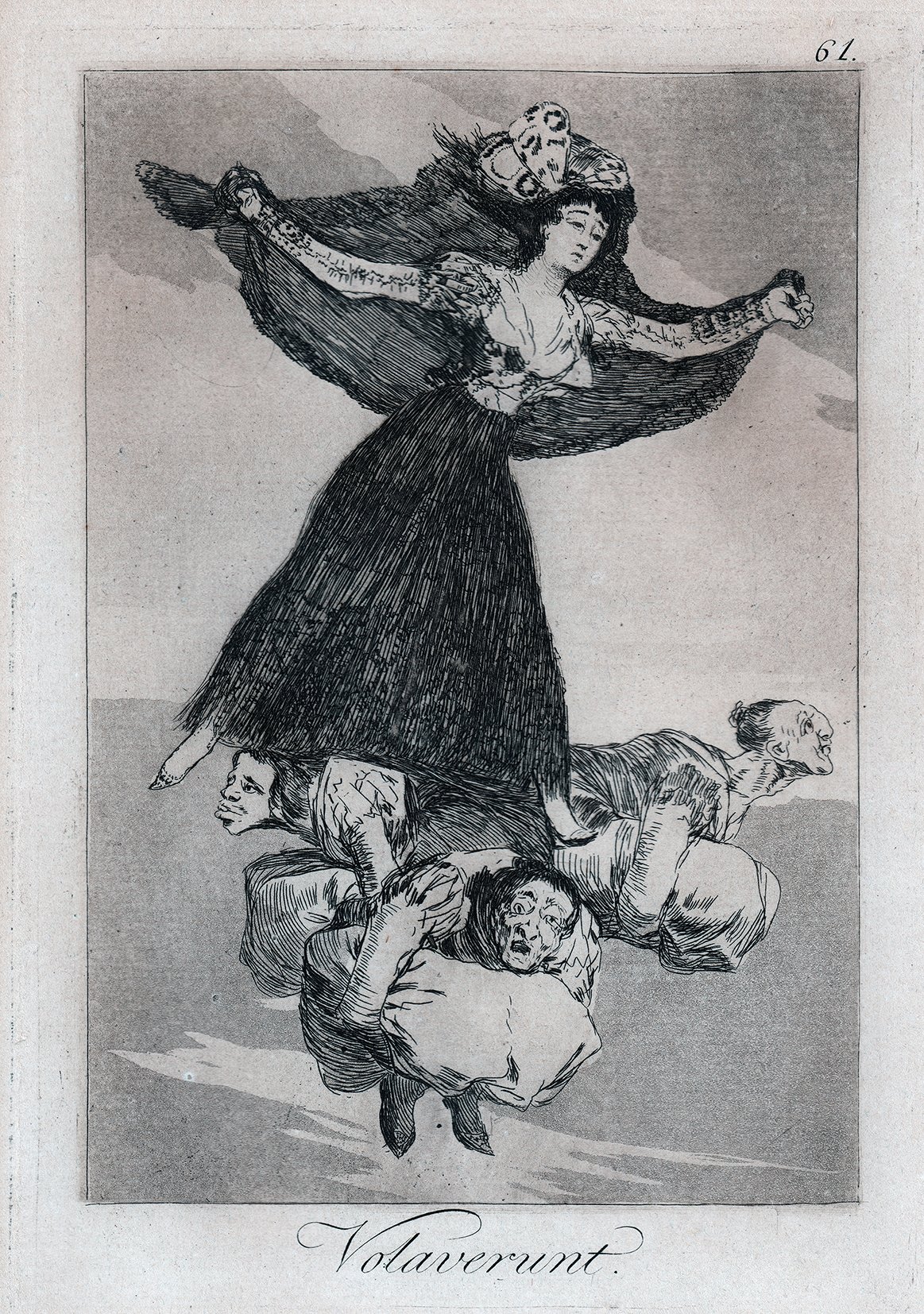

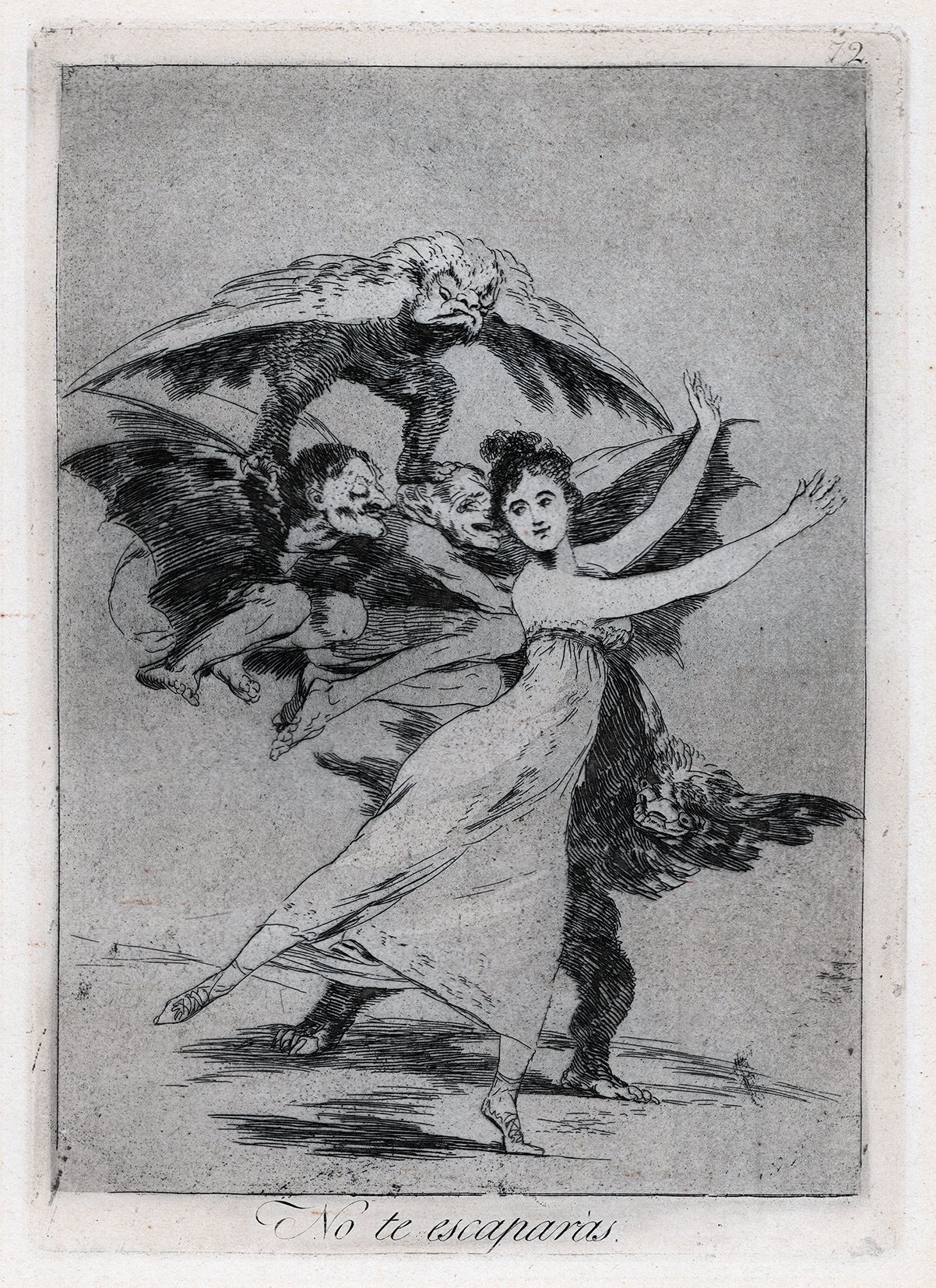

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

There etchings by Francisco de Goya from the Los Caprichos ("caprices" or "follies”) series shown below are thematically linked in expressing Goya’s mostly negative attitude towards women: Volaverunt, Hasta la muerte, No te escaparás and Ya van desplumados. The National Gallery of Victoria, in Australia, has a rare first edition of the full 80 plate series titled Los Caprichos. You can read an essay by Frank I. Heckes on how the series came about and why there is so much conjecture about the meaning of the various plates. NGV ART JOURNAL 19 2 July 2014. Images of all the 80 plates are on the Royal Academy Website.

Francisco José de Goya (Spanish, 1746 -1828) They have flown (Volaverunt.) Plate 61 from 'Los Caprichos' 1797 - 1799. Etching, aquatint, drypoint on heavy laid paper, with watermark Goya wearing a cap (tenth edition) plate 220 x 150mm. sheet 365 x 260mm. (Private collection)

Volaverunt is one of the iconic images from Los Caprichos and one of the prints that has received the most commentary from art historians. Its attraction is derived from the formal harmony of the image, as well as its influence in the construction of the romantic myth of the artist´s supposed intimate relationship with the Duchess of Alba. In contemporary accounts, the duchess was described as a stunningly beautiful woman, whom the painter portrayed on several occasions, most recently before the publication of Los Caprichos in his portrait of her from 1797, dressed in black and pointing toward the inscription Solo Goya (Only Goya) on the ground before her (Hispanic Society of America, New York). Almost every interpretation of the female figure in this print identifies her with the duchess, explaining the image as a bitter criticism from a spited lover. As is typical of other prints in the series, the Latin title Volaverunt suggests several meanings, for in addition to its literal translation, They have flown, it can also allude to something lost.The hypothesis that Goya is saying that the Duchess of Alba has flown away forever depends on the butterfly wings -a symbol of inconstancy according to a longstanding poetic tradition- emerging from the back of the young woman´s head. But the butterfly may also signify fragility, or that which is ephemeral and changing; it is also conceptually tied to the idea of immortality in the sense of passing on to a new life. Because of its mutable nature, the butterfly is associated with Fortune, and in Cesare Ripa´s Iconologia -an emblem book that provided generations of artists in Europe with their main source of iconographic symbolism after its publication in 1593- the allegorical figure of Imprudence is represented with butterfly wings. In its simplest sense, the butterfly embodies femininity, and since its wings serve to fly, their inclusion in an image of a woman flying seems to be an obvious connection.Tempting though it may be to interpret this print as a commentary on a romance between the duchess and the painter, there is no proof that such a relationship ever existed, nor are there any objectively clear elements in Volaverunt that would allow us to identify the woman as the duchess. A comparison with other female figures in the series suggests a different conclusion. The woman here is wearing the walking dress Goya used for prostitutes in other prints. Significantly, the woman´s legs are spread and her neckline bare. The trio of grotesque characters propelling her flight appear to be witches. Indeed, in the ordering of the prints, this one is included among the scenes of witchcraft. Goya´s witches are a variant of the depraved go-betweens that incite prostitution and lead people to vice. From this standpoint, we may view the young woman in Volaverunt as flitting from man to man as a butterfly between flowers, driven in her flight by the witches (Blas Benito, J.: Portrait of Spain. Masterpieces from the Prado, Queensland Art Gallery-Art Exhibitions Australia, 2012, p. 208). Source: Prado Website.

Francisco José de Goya (Spanish, 1746 -1828)

Until Death (Hasta la muerte.) Plate 55 from 'Los Caprichos' 1799. Etching, aquatint, drypoint on heavy laid paper, with watermark Goya wearing a cap (tenth edition) plate 220 x 150mm. sheet 365 x 260mm (Private collection) . Widely acknowledged as one of the most important Spanish artists of the Romantic era, Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) was a supremely innovative printmaker, thanks to his experimentation with the newly invented aquatint process. Aquatint produces areas of tone by applying powdered resin to the metal printing plate, and Goya combined this with etching and burnishing to produce images of great tonal depth, employing theatrical contrasts of light and dark.

This is Plate 55 in a series of 80 etchings by Goya called Caprichos. An English sale catalogue of 1814 described Caprichos as representing ‘every kind of vice from the highest to the lowest classes…the avaricious, lascivious, cowards, bullies…prostitutes and hypocrites’. These caricatures, attacking the familiar targets of lawyers, doctors, soldiers and priests, were deeply unpopular with the Spanish Inquisition.

Here an elderly woman admires her reflection in a mirror, as a number of young onlookers suppress their mirth. It represents an age-old topic for social criticism, the deluded vanity of old age, as the wizened crone clings to the illusion of her beauty ‘Until Death’.

Although Goya enjoyed enormous popularity in France, admired by the poet Chales Baudelaire and painters including Édouard Manet, the English were slow to appreciate his work. The critic John Ruskin, disgusted by their ‘immorality’, burned a copy of the Caprichos in 1872, and the National Gallery acquired no works by him until 1896. The antiquarian, Francis Douce (1757–1834) was one of Goya’s few early admirers, owning two copies of the Caprichos. Douce bequeathed his collection of prints to the University of Oxford in 1834 and the majority of these were transferred from the Bodleian Library to the Ashmolean Museum in 1863. Source: Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Francisco José de Goya (Spanish, 1746 -1828)

You will not escape (No te escaparás.) Plate 72 from 'Los Caprichos'

1799. Etching, aquatint, laid paper, (eighth edition) plate 220 x 150mm. sheet 365 x 260mm sheet c. 380 x 270 mm (Private collection)

This plate can be grouped with a number exploring "devils and witchcraft". Goya presents the representation of a young woman persecuted by witches and creatures of the night. The pantomimic gesture of flight can be interpreted as the unconscious search for adventure, or sexual innuendo. Source: Prado Website.

Francisco de Goya (1746-1828). Disparate Pobre (Poor Folly) [Two Heads are Better than One], plate 11 from Los Proverbios 1864 [plate worked 1816 -23] etching, burnished aquatint, drypoint and burin, 25 x 35 cm

Plate 11: two headed woman looking back towards cowled figure, but approaches group of old women on steps. [BM description] (Second ed printed at Real Academia of Fine Arts San Fernando, Madrid.)

Max Beckmann (1884 –1950)

"King Jerum, Queen Würgipumpa, Ursulus and the flying church" . 1923 drypoint on laid paper. 19 × 14.5 cm (37.5 × 26.5 cm) Signed.

Hofmaier 296 A (from B) .–

Proof outside of 220 copies. Sheet 6 (of 8) of the illustrations for Clemens Brentano: Fanferlieschen Schönefüsschen. Berlin, Verlag Fritz Gurlitt, 1924. [3285]

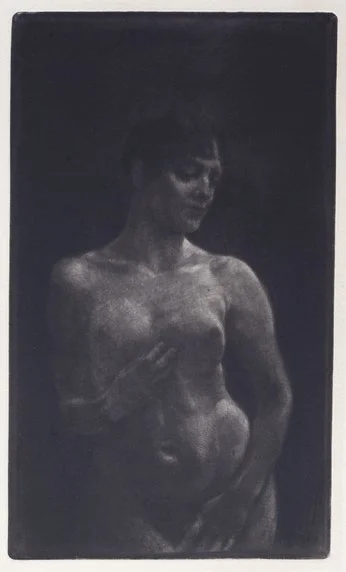

Max Klinger (1857 – 1920) Weiblicher Akt in Schabkunst (Female nude in mezzotint) 1891 Etching mezzotint, plate 28.9 x 16.9 cm : sheet c.45 x 32 cm.

Description from BM of the second state in their collection this is the third final state: Singer states that Klinger began the plate as an etching (1st state, of which Singer knew no examples) but when that proved unsuccessful, he worked it over with a mezzotint rocker. BM print is from the 2nd completed state, of which Singer knew of only a dozen or so impressions. This is the 3rd state which is unchanged and was issued as a subscribers' edition for the Deutscher Kunstverein with the letterpress in the lower border 'Max Klinger/ Weiblicher Akt' on the left and 'D.K.V.' on the right. Klinger made only three mezzotints, all in 1891.

Kathe Kollwitz (1867 – 1945) Self-Portrait (SELBSTBILDNIS) 1912, Aquatint and soft ground etching on paper (seventh state)13.9 × 9.9 cm signed

Helen Farmer (1888 - 1970) Cobbitty Farm c.1925 etching, plate 18 x 19.3

Helen Farmer was part of the Golden Age of Etching in Australia 1920s and 1930s

Primary evidence in:

Lionel Lindsay “the Art of Etching” Art in Australia [Australian and NewZealand Etching Number] No 9 1921. Read in TROVE

Ure Smith Art in Australia special Etching Number, September 1925 (Third series, No. 13) This issue contains “A COLLECTED LIST OF ETCHINGS PUBLISHED IN AUSTRALIA WITH THE NUMBER OF PRINTS CONTAINED IN EACH EDITION AND ITS DATE OF ISSUE TROVE”

The list runs to ten pages of tightly spaced small font titles. Most favoured edition size is 50.

‘THE REMBRANDT ETCHINGS IN THE MELBOURNE ART GALLERY” ( Art in Australia 1 November 1934)

Copyright © Ross Woodrow --All Rights Reserved 2026

![Man In A High Cap [Portrait Of Rembrandt’s Father]1630/c1800 impression. Etching, initialled and dated in plate upper left, 10.1 x 8.5cm.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b9e00fd506fbe9caf83a4b6/1653451027915-0ECHI9WGSCGYWILPBBWG/Untitled-1.jpg)

![Old Man with Beard, Fur Cap, and Velvet Cloak, [circa 1631] etching with drypoint, impression of New Hollstein's second state (of three).](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b9e00fd506fbe9caf83a4b6/1653450517388-WPDS08KZLR8OQICB4SIZ/secondState.jpg)

![Gerrit van Schagen (Dutch, c. 1642 – 1690) after Jacques Callot (French, 1592 – 1635) The Hanging. Plate11 from De Droeve Ellendigheden van den Oorloogh [The sad miserableness of the war] c.1670](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b9e00fd506fbe9caf83a4b6/1653572215369-DV0JPS7ZP0NC80TVF5ZB/JCmis-11.jpg)

![Gerrit van Schagen (Dutch, c. 1642 – 1690) after Jacques Callot (French, 1592 – 1635) Discovery of the criminal soldiers plate 9 [The sad miserableness of the war] c.1670 (Copy)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b9e00fd506fbe9caf83a4b6/1653572478423-7OJB1JVX2ALG9Z2MRIG4/CallotCopy-soldiers.jpg)